Digital scan back

A scanning back is a type of digital camera back. Digital imaging devices typically use a matrix of light-sensitive photosensors, such as CCD or CMOS technologies. These sensors can be arranged in different ways, like a Bayer filter, where each row captures RGB components, or using one full-sized layer for each color, such as the Foveon X3 sensor. The main difference between both approaches is in the way the final image is constructed. In a Bayer filter, since each pixel can only record one color, the resulting pixel has to be constructed with information from its neighbouring pixels using demosaicing algorithms. Using one layer per component instead measures all color components for each pixel, so the resulting pixel is the value measured in every layer for that pixel. This approach delivers better image quality, because all information is actually measured, as opposed to being guessed. The downsides compared to a Bayer filter are that it is much more expensive, because N layers of sensors have to be used, and the resulting digital image is much smaller (by a factor of N). However, since the image is more accurate, more work can be done on it. An image from a Bayer filter is usually downsampled to improve quality, and when upsampling it shows artifacts much faster.

A digital scan back takes a similar approach to the second type of photosensor, but instead of using one matrix for each component, it uses one array per component. This translates to a 3xN sensor matrix, where N is typically a large number (between 5,000 for earlier models and 15,000 for newer models), which is then placed vertically in a holder. To take an image, the sensor travels the x axis, taking one exposure per point.

Contents |

Advantages

The main advantages of this technology are the extremely high image quality and the huge resulting files. This translates to very accurate color reproduction, because every pixel is measured individually, allowing printing in very large sizes without loss of detail. Previously only large format film cameras could print to similar sizes. Scan backs also have the advantage of not being subject to light fall-off due to off-axis lens positions, so wide angle lenses and perspective shifts on the camera can be used without issue. A somewhat less obvious advantage lies in that scanning backs are typically created using trilinear CCD's. This means that for every pixel position a separate measurement is taken for red then green then blue. This results in a much higher effective resolution than a similar resolution image created by a mosaic sensor such as those on nearly all more typical digital cameras. (With the notable exception of foveon)

Disadvantages

The downside of capturing images this way is the amount of time it takes. Even at the fastest speed, the time taken to make a complete exposure is measured in seconds or minutes, because even though the shutter speed could be 1/1000 s, it has to be taken literally thousands of times. This makes it very inappropriate for moving subjects, such as sports, nature, or city life, and is practically restricted to still life, art reproduction, and landscapes.

Another downside is that most of these backs have to be used tethered to a computer. One reason is that there would be no other way to know when critical focus has been achieved, and the second reason is the huge file sizes, measured in hundreds of megabytes or even gigabytes. High end 4 GB Compact Flash cards can only store a handful of images.

Example

Let's say we have a 10,000 pixel array, and we want to take an image with a shutter speed of 1/50s, and 48 bit per pixel (16 bit per component) to achieve maximum quality.

Assume each individual pixel has a width and height of 6 μm per 6 μm. The array will be 6 μm wide and 6 cm high. Now we place this array in a holder 6 cm high per 6 cm wide. That means we can evenly divide the x axis in 10,000 points, so the array has to take 10,000 exposures. To capture an image the sensor would start at x=0, take one exposure at the selected shutter speed, move to x=1, take one exposure at the selected shutter speed, and so on until x=9,999.

Now instead of doing it with one array, we do it with three arrays at the same time (one for each component in RGB), where the first array would be making an exposure at x, the second at x-1, and the third at x-2. The resulting image would be 10,000 x 10,000, or 100 million pixels, with full color information for each pixel.

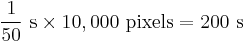

- The total exposure time will be at least:

or almost three and a half minutes. A real sensor would have to take into account an accurate movement to the next point, stopping and waiting to reduce vibration, take the exposure, and so on. This overhead is required, and can double or triple this time.

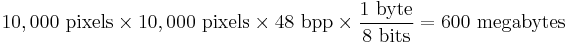

- The final image size would be:

The newest sensors can achieve even bigger file sizes, up to several gigabytes.

Manufacturers

- Better Light, specializes in digital scan backs.

- Phase One, has the PowerPhase FX+ in their lineup.

- Anagramm.

- Kigamo.

- Pentacon, German company has a range of scanning cameras including the Scan 3000 & 5000 series.